My Thoughts on the Controversial Cochrane Mask Study

May 01 2023

Community masking was one of the most hotly debated topics during the pandemic. And the recent Cochrane study made the topic even more controversial by questioning the efficacy of masks. Here follows my take on this critical study:

What did they do?

Cochrane is a non-profit organization that conducts systematic reviews on healthcare topics. A Systematic review summarizes a collection of studies on a particular topic and thus shows the totality of the evidence. And Cochrane reviews are considered the gold standard due to their rigorous methodology.

The first mask review was published in 2001, and it has been updated in 2009, 2020, and now in 2023 (1). In 2020, the authors decided to only include randomized controlled trials instead of observational studies, which led to the inclusion of two studies that took place during the pandemic.

The questions they asked:

- Can surgical/medical masks prevent the spread of respiratory virus infections and lab-confirmed infections?

- Can N95 masks prevent the spread of respiratory virus infections compared to medical/surgical masks?

- Can hand hygiene (hand washing & sanitizer use) prevent the spread of respiratory virus infections?

So what did they find out about masks?

- Viral respiratory illness: For surgical masks, the study concluded “Wearing masks in the community probably makes little or no difference to the outcome of influenza‐like illness/COVID‐19 like illness compared to not wearing masks risk ratio (RR) 0.95, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.84 to 1.09; 9 trials, 276,917 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence”

- Laboratory‐confirmed viral respiratory illness- Similarly, for lab confirmed outcomes showed similar results that masks probably makes little or no difference.

I have highlighted two words “probably” and “little or no difference” since these are the key words that say everything. I have omitted N95 masks and hand hygiene questions for the sake of brevity.

What do the results really mean?

Several articles from major news outlets and experts have commented on the review, but few have interpreted it correctly. It is important to note that Cochrane uses a specific methodology called GRADE to summarize and communicate the results. And without having a decent understanding of GRADE, the results can be very confusing.

GRADE mainly uses two concepts to summarize study findings.

1. Size of the difference

2. Certainty rating

- Little to no difference: The size of the difference here of 0.95 is considered to be trivial by the authors hence the use of “little to no difference”. But what the heck does 0.95 mean? I have yet to see anyone who interpreted these numbers properly

- 0.95: A risk of 0.95 means a 5% reduction in infections. However, this does not mean that 5 out of 100 people will benefit. Rather, if 1000 people wore masks, 8 fewer people would be infected or would receive a benefit.

- Confidence interval (CI): The confidence interval (CI) of 0.84 to 1.09 shows us the precision or uncertainty in the results. This means that the 5% estimate could range from as low as 26 fewer people being infected to 14 more people getting infected (out of 1000).

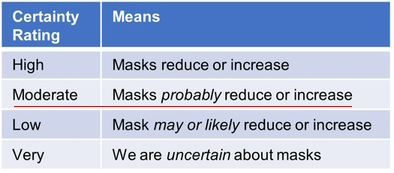

- Moderate certainty means? But how certain or confident are we about this estimate of 5% reduction? That’s where the GRADE certainty ratings come in. As shown below, there are 4 certainty criteria (High, Moderate, Low, & Very low) which communicates different degrees of confidence in the results. Every review starts out at high certainty and get downgraded based on how well the study was conducted based on 4 domains.

Here the certainty rating was downgraded from high to moderate because of high risk of bias (or poor study quality) for viral illness and for the lab‐confirmed influenza/SARS‐CoV‐2 for imprecision. Thus, combining the magnitude of benefit and the certainty rating, the authors end up with the statement of masking “probably” has “little to no difference”.

Bear in mind that a rating of high certainty reviews is usually seen for drug trials and the majority of the Cochrane reviews end up being low or very low certainty. A moderate certainty for behavioral intervention is pretty good and pretty damning evidence against wearing masks. This is why the lead author of the study in another article wrote, “There is just no evidence that they make any difference. Full stop.”

So should you stop wearing masks?

My thoughts:

It is important to note that the GRADE approach requires judgement and could vary between individuals. What it lacks in objectivity is supposedly made up in transparency, i.e, how authors came to their decisions. Below I show some alternative conclusions that are equally correct within the GRADE approach:

Viral respiratory illness

- Mask may reduce viral infections: Since the authors haven’t transparently stated what is trivial or an important reduction, they could have very well concluded that surgical masks may show an effect based on the 5% reduction. And since the interval captures both benefit (16%) and harm (9%), they could downgrade it for imprecision and end up with a “Low” certainty than moderate certainty. This conclusion makes more sense since we don’t know what is trivial or a small, important effect is, but we know there is some non-zero (5%) effect/reduction.

- Is 5% trivial: A good question is 5% a small, but important or trivial benefit ? While a reduction of 5% or 8 fewer people out of 1000 may seem trivial from an individual perspective, it could have a significant impact from a population or public health standpoint, especially for a highly contagious serious infection like COVID-19. It’s important to remember that mask mandates were not just meant to prevent infection in the wearer, but also to prevent the spread of infection to others. This is totally different from our typical diseases, like heart disease. You don’t transmit heart disease or diabetes, do you? To put these numbers in perspective, the Pfizer COVID vaccine showed an absolute reduction of 0.7% (7 fewer people out of 1000), but we know that number could quickly escalate to 500 out of 1000, if left unvaccinated. Statins, the number one selling drugs, show 10 fewer deaths and 13 fewer heart attacks in 1000 people taking them for 4-5 years (3). The bottom line is that the authors could have concluded that there may be an effect/reduction and let the readers decide for themselves if this effect is important or trivial.

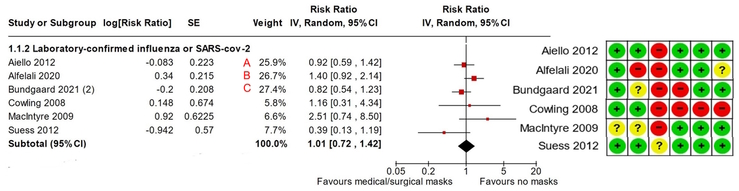

Lab-confirmed viral illness

- Risk of bias: The authors downgraded the certainty rating for risk of bias for the outcome of viral illness. However, they did not downgrade for lab-confirmed outcome and haven’t transparently justified it either. All the studies are clearly of “high risk” of bias as shown by the red circle. The 3 studies contributing the most weight (A,B,C) is also at high risk.

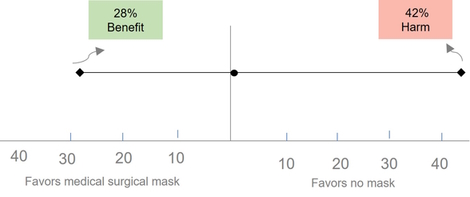

- Precision : Several folks have argued that the confidence interval (CI) for lab confirmed outcome is quite wide (0.72 to 1.42), representing a 28% decrease to a 42% increase, and therefore the results should be considered uncertain. This uncertainty is related to the threshold that the authors consider to be trivial or important, which they have not explicitly stated in the article. Interestingly, the authors concluded that hand hygiene “may reduce infection” with a 14% reduction (0.86). If a 14% reduction is good, then a 28% to 42% change from masking would certainly show large benefit and harm (42% is 3 times 14%!), right? This would mean that the certainty rating should be downgraded by 2 or 3 levels, and not just by one, indicating low or very low certainty about the benefits of masking. Even without GRADE guiding us, it makes a lot of common sense to say that we are uncertain, since the true effect is equally compatible with a large benefit and harm. This is what GRADE recommends as well, as shown below in their latest paper on precision. (2)

“Using the CI approach, when the CI is wide and considerably cross the

threshold(s) of interests (i.e., one or both boundaries of Cls suggest

inferences appreciably different from point estimate), one should consider

rating down two levels for imprecision, and when the Cl is very wide that the

two boundaries of Cl suggest very different inferences, one should consider

rating down three levels for imprecision.”

So, considering the serious risk of bias and imprecision, the lab confirmed outcome could have easily ended up to be “very uncertain”. Or in other words, we could say are very uncertain about masks.

A few other criticisms:

- Low adherence: Some folks have argued that since the authors reported low adherence t0 mask wearing, the conclusions are not very credible. But this is exactly how real life works. If you ask people to wear masks, some will, some will not, and many will wear them improperly. It is called the “Intention to treat” approach, which has been the standard approach for analyzing trials for over 100 years!

- Promote mask wearing vs. mask wearing: The Cochrane editor and a few others have argued that the review is about “promoting” mask wearing rather than wearing masks. While this is true, it’s also true for most behavioral interventions, like physical activity, nutrition, drugs and so forth. Therefore, if we adopt this argument, it follows that we should update all reviews along similar lines.

Decision making: On a final note, decisions about wearing masks, or any interventions for that matter, are not just about looking at the benefits. Instead, decision making involves weighing the benefit, risk, and burden, which in turn depends on the values and preferences of the individual. For example, a trivial benefit for one person could be an important benefit for another, which explains a lot of the polarized opinions on this topic.

Conclusions:

In summary, instead of concluding masks probably don’t work, conclusions for this review could have ranged from “wearing masks in the community may reduce infections” to “we are very uncertain of the effects of mask wearing on infections”. This also means we need better quality studies and more of them.

So, don’t throw away your masks!