There were a lot of comments, but the most sensible counter argument is how can there be an obesity epidemic if it is largely genes? Hence it is rather clear that obesity is largely due to our environment. And this is the argument almost all studies make to counter the biological basis of obesity. Here I am going to drill down further into the data and show exactly what these numbers mean and why is it is largely your genes.

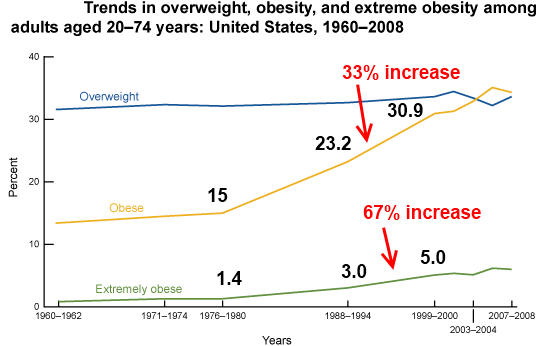

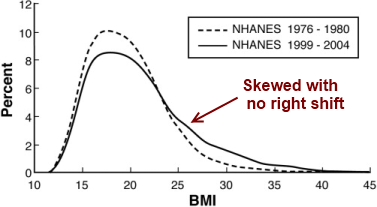

In the 1980's and 90's, as shown in the graph from CDC, a lot of people (20-74 yrs) gained weight and moved into the obese and extreme obese category. This is shown as a steep rise in the obese and severely obese lines in the graph. If you calculate, it shows a 33% increase in obesity and a 67% increase in extreme obesity in the 90's compared to the 80's. This sharp increase in the percentages prompted the researchers to call it an epidemic.

This was the same for childhood obesity too. For the age group of 6-11 there was a 73% increase and a 100% increase for the age group 12-19.

These numbers are huge and gives a picture of people all over in US just gorging on food and lying around doing nothing but getting fat.

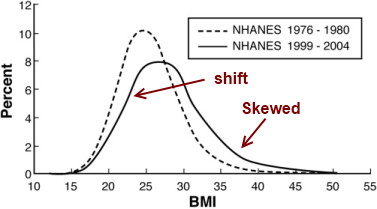

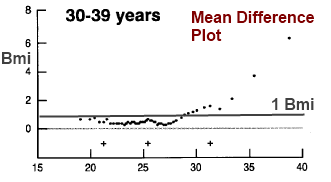

It is hard to tell this difference from the frequency curves. They are in fact smoothed (curve smoothing) to give those clean curves. The researchers hence used mean difference plot technique to look at the increases in weight based on the BMI levels. What they saw was less than 6-8lbs (1 BMI) increase for the people in the lower BMI catgeory, while almost 3-4 times this amount for the obese and extremely obese category. This graph for 30-39 year olds men (1976-80 till 1988-94) shows the general trend n the MD plots, though the differences are smaller in certan subgroups. This shows that even the average weight of 6-8 lbs in a decade is is largely due the obese and extremely obese category ganng weight. So people who are at normal or overweight BMI might have increased an average of 4-5 lbs at the most in the 90's.

Ths clearly shows that for folks who are genetically predisposed to obesity, the toxic environment seems to make it worse. For people who are not genetically predisposed, the very same toxc environment is not making any big difference. Why is that?

If we lower the calories and increase physical activity, the obesity trends will come down. The curve will be shifted to the left and less skewed; there will be less obese people, and obese will be less obese. But the shape of the curve will remain the exact same as in the 1970. That simply means there will be still obese people and lean people! And why is that? The short answer is 'genes'.

| Sun January 15, 2012

Hi Anoop, so its gene expression. Some people will be fatter or skinnier relative to each other in all worlds. But in a world where there is fast food on hand (without having to cook it for an hour first, for example) then body masses are greater, because the gene for obesity is expressed to a greater extent.

The study kind of gives people a cop out in that it justifies the genetic component, but its a bit like saying “Cancer runs in my family, all of the smokers died from it”

Anoop | Mon January 16, 2012

Hi Owen,

Thanks for the comment.

I think you make it sound like obesity is largely genetic is just common knowledge. And all these years we were all blaming it on fructose, carbs, portions sizes, and whatever and hiding the truth just so that obese people don’t “cop out”. This is probably the very few articles which points the finger at genetics.

Obesity is always and still considered as a stigma. They have been discriminated and judged everywhere, in schools, workplaces, and even by health care professionals. This is largely because we still think obesity is all about a personal choice. I know when my clients lie to me. You know why? Because they are humiliated to say that they ate again because they were just hungry! They are convinced that obesity is all about right choices, lifestyle because that’s what they keep on hearing from everyone. And if they cannot lose weight, it is nothing else but their personal failing.

And read the practical recommendations please. I have clearly written how much they should lose, and when they can lose more, and why it is important to exercise and eat healthy.

And I am pasting the conclusion of the Tara parker article which is apt to this discussion:I have highlighted the important part in bold which is what is exactly lacking in our society.

So where does that leave a person who wants to lose a sizable amount of weight? Weight-loss scientists say they believe that once more people understand the genetic and biological challenges of keeping weight off, doctors and patients will approach weight loss more realistically and more compassionately. At the very least, the science may compel people who are already overweight to work harder to make sure they don’t put on additional pounds. Some people, upon learning how hard permanent weight loss can be, may give up entirely and return to overeating. Others may decide to accept themselves at their current weight and try to boost their fitness and overall health rather than changing the number on the scale.

For me, understanding the science of weight loss has helped make sense of my own struggles to lose weight, as well as my mother’s endless cycle of dieting, weight gain and despair. I wish she were still here so I could persuade her to finally forgive herself for her dieting failures. While I do, ultimately, blame myself for allowing my weight to get out of control, it has been somewhat liberating to learn that there are factors other than my character at work when it comes to gaining and losing weight. And even though all the evidence suggests that it’s going to be very, very difficult for me to reduce my weight permanently, I’m surprisingly optimistic. I may not be ready to fight this battle this month or even this year. But at least I know what I’m up against.

| Mon January 16, 2012

The study talks about controlling your diet to within 7 calories a day to prevent middle-aged-spread. This is another case of an average concealing the range. In reality people pig out over holidays, birthdays etc etc and without an opposing training regime, the gained pound never goes away and the mass increases.

Anoop | Mon January 16, 2012

Hi Owen,

Which study are you talking about?

Your body controls your body weight very tightly. If you eat a lot, it speeds up your metabolism. If you lose weight, it slows your metabolism.

It is the very reason why most people maintain a stable body weight in a year. And we are talking about balancing a million calories to a precision of 99.6%!! This amazing example is just enough to show how there is a strong biological basis to obesity. Did you read the first article Owen?

Thanks for the discussion.

| Mon January 16, 2012

I don’t disagree with the notion that genes (actually gene expressions, unless you pin-point the obese-gene) are the most important factors in bodyfat gain, but I doubt that the speeding and slowing of the metabolism is the main regulator of fat gain. Hunger suppression and activation is more likely the main regulator. I am not saying that there are no fatter people with lowered metabolisms, but these are rare and so unlikely the main mechanism to explain the statistics above.

Just cause:

http://eugenization.wordpress.com/2007/08/10/can-you-outsmart-your-genetics/

(these twins don’t discredit the articles, but show the influence of environment in an extreme case.)

Note that Ewald is not as big as Ronnie Coleman. 😊

Somehow the fact that almost none of us have even the potential to get close to where elite (natural) bodybuilders are in terms of leaness and muscularity is accepted with ease, but as soon as we look at the other end of the spectrum fat people should just work harder and eat less.

| Mon January 16, 2012

Yes, it came through!

| Mon January 16, 2012

Hi Anoop,

It’s not clear from your article as to how you arrived at the 6-8 lbs per decade figure - can you elaborate on your methodology please?

Assuming that figure is correct, it still represents a huge problem; 8 lbs over three decades is 24 lbs. Given that a good portion of that weight gain is likely to be adipose tissue and not lean tissue (reflecting the higher rates of sedentary life), and given the strong association between increased adiposity (especially central visceral adiposity) and certain morbidities (e.g. Type 2 diabetes), a 24 lbs average weight gain over the last 3 decades is indeed consistent with the label “obesity epidemic”.

And that’s just for the ‘average’ folk. As you point out, the larger weight increases attend the obese category. For these folk, the last 30 years have been disastrous in terms of obesity-related co-morbidities, with Type 2 diabetes becoming rampant. This fact alone is enough to show that genetic factors are not relatively salient - prior to 1980, these obese folk still had the genes that promote obesity; but now, due solely to the increasingly obesogenic environment, they’re also suffering from rapidly rising rates of co-morbidities.

As I’ve said previously with respect to the obesity problem, genes are a permissive factor, while the environment is the regulating factor. This is why individuals from certain cultures that are uniformly lean (e.g. Okinawans) often become fat(ter) when exposed to a ‘Western’ diet. Their genes don’t change, but their diet does (driven by the environment).

We only get as fat as our environment lets us (reflecting the trope that there are no obese people in a gulag), irrespective of our genetic make-up.

Human beings are generally unsuccesfull in overturning the pull of their environments (e.g. education, religious, financial philosophy). The obesity problem simply reflects this fact once more.

Cheers,

Harry

Anoop | Mon January 16, 2012

Hi Fulldeplex,

Thanks Fulldeplex!

Hunger I think is the driving factor in obesity.

From what I have read, all the obesity genes seems to be working at the hypothalamus to increase or decrease appetite (leptin, cck, ghrelin and so forth). And this is what I don’t understand when people casually say genes don’t express without the right environment. In obesity, people eat because they are freakin hungry! It is not that they accidentally started eating more or just decided to get fat oneday. And there is surely a slowing of the metabolism too. Leptin strongly acts on both side of the equation. It could be less activity, less NEAT (non exercise induced activity thermogenisis). It is the same reason why identical twins gain different weights when they are put on the same calorie intake.

And I have seen that twin picture. We could wrong at many levels to compare muscle and fat. They are just so completely different physiologically. And I don’t think anybody is having trouble losing or gaining, it is the maintaining part for years that brings out the true colors. They probably look the same after 10-15 years unless they are ready to train like that for the rest of their life. And a “natural” german strength athlete in the 1960’s just don’t sound right!

And excellent point.

I was about to write this before. Why can’t all the normal people have a six pack or why can’t all the people who weight train look like Layne Norton or Doug Miller? After all, it is all about lifting more and eating right and choices, right?

Anoop | Mon January 16, 2012

Hi Harry,

First, if you look at the tables, the difference in average BMI is around 1.2 lbs for the 1976-80 till the 1988-94 survey. Second, atleast half of this gain is due to the outliers, so you can cut that to 4-5 lbs (you missed this part). And this what is causing the obesity epidemic! You won’t say America is getting richer, when it is largely because the rich getting rich, do you?.

All these prevalence and BMI data are on the CDC website. You just have to go read it. I think I have given you a lot of studies.

Now don’t tell this article is an example for environment. Normal people seems to be genetically protected while obese seems to be genetically predisposed in the SAME environment. If environement played the larger role, everyone should gain it equally.

And this a population data based on cross sectional studies on different samples. It is really hard to say the weight gain for an individuals based on it.

You are wrong about Okinawins being lean due to genetics and getting fat due to the environment. In fact, people from the aboriginal tribes are considered to have genes predisposing them to obesity. This is because they were brought up in environment where food was scarce and hence the genes re very susceptible to fat gain. This is the same reason cited for pima indians and the pacific island tribes gettng really obese. And I wrote this in the first article.

| Mon January 16, 2012

I suppose you get this data from an article/articles, I’d love to read it.

I liked this piece more than the first one as it fits very well with my belief of an interaction between genes and environment. But you do realize that what you’re saying here is that those genetically predisposed to obesity get obese because the environment is changing. While those not predisposed are unaffected/less affected.. that was basically my argument in the previous piece.

Anoop | Mon January 16, 2012

Hey Karky is back!

Thanks!

The article says that people who are ‘already’ obese will be more obese. These people were obese back in the 1970’s even when the environment was not even obsegenic. The percentage of overweight people hasn’t changed at all for 30 years..

And I would agree if you take the obese and put them in a hunter gatherer environment, they might look normal. I agree with you there. When there are people dying without food in the world, I just see all this processed and cheap food as a success story in human history. I think the word “cause” is making all this confusion.

I got the first idea from Jeffrey Friedman’s paper (Modern science versus the stigma of obesity. He discovered Leptin. But I never really looked into it. It is one of those areas where people have an opinion based on personal observations and anecdotes and nothing will make it budge. I was one among them until I started looking more into it.

There is no paper which really question this concept. The papers are mostly which talks about how studies have overexagerted the epidemic is based on the mortality for overweight people. You might have read it or heard about it. That is one of the big controversies which gave CDC a bad name. Katherine Flegal is lead author of all these obesity prevalence papers. I looked at those papers to get those numbers to see if Friedman was right. And when you look at the other all the evidence, just the stability of weight, people cannot maintain their weight lost, in animals it is just hard not to see the large influence of genes. Most people have just conveniently overlooked all those in my article and just focused on the obesity epidemic.

And one of the reasons why they don’t really emphasize this in CDC papers is because of Rose’s prevention strategy for preventive medicine, which is used all over the world. According to Rose whether the high risk individuals are being largely affected doesn’t matter; we need to focus on the population as a whole than a select group. And this will make the curve shift the left. Hence all these strategies aimed at the population. This is true even for childhood obesity where the curve is skewed with no shift. And my argument is largely talking about it is largely genetics.If it is genetics or not, the CDC’s people have to do something about it. So no point ,besides giving a passing reference, concluding it is largely genetics in their papers you know.

And if you look at the obesity prevalence, it is slowly leveling off now. In men, it is almost the same for 5 years, while in women and kids it hasn’t changed for 10 years. We don’t know if this is due to all the health promotion, gastric surgeries or just obese people hitting their genetic ceiling.

| Tue January 17, 2012

Hey Anoop:

As always, excellent interpretation of research. Michael Rosenbaum and his group at Columbia University have done a lot of good research in this area. Not sure whether you’ve seen his recent review. A really good read:

http://www.nature.com/ijo/journal/v34/n1s/full/ijo2010184a.html

Hope all is well!

Brad

Anoop | Tue January 17, 2012

Thanks Brad for the comment! It s good to know we are on the same page here.

I will have to check it out. Another one is Sadaf Farooqi who has a lot to say about obesity and genes.

| Tue January 17, 2012

Hi Anoop,

There’s a saying here that springs to mind (first heard it from Gordon Livingston), “When the map and the ground do not agree, the map is wrong”.

And, in the case of obesity statistics, I think the map is clearly wrong. The proposition that the average North American male is only 2 or 3 kgs heavier than they were 30 years ago is so discordant with my real-world observations that I am compelled to assume a flaw in the data collection. Perhaps some kind of sampling error is at play (quite likely, given the lack of official records on obesity), or that we are seeing some typical problems with data collection when dealing with stigmatised pathologies (e.g. doubly labelled water studies show that overweight/obese under-report energy intake).

Observe the popular culture media from the 70s (e.g. TV shows, documentaries, crowds at sporting events) and compare it to those of today; people are noticeably larger and fatter across the board (not just the obese becoming very obese).

This is also reflected in sizings of clothing manufacturers…the ‘normal’ range has shifted dramatically to reflect the changes in the general population.

And the prevalence of childhood obesity can be testified to by any primary school teacher…whereas there was generally only one or two chubby children in each class 30 years ago (the relative novelty of their body shape explaining their poor treatment at the hands of leaner classmates), there are now more like one quarter of each class that are overweight and/or obese.

But more importantly, the pathological record shows the undeniable expression of weight-related morbidities, most prominent among them Type 2 diabetes (also increased CVD, hypertension, arthritis). If the rise in obesity is as gentle as the statistics suggest, we would expect to see little impact on weight-related pathologies, not the rapid increases in prevalence that we are in fact seeing.

Until we can get some solid statistical figures (the NHANES data is not ideal, given its reliance on relatively small representative sampling and extrapolation) I think it would be wise to trust what we can see all around us, rather than focussing unduly on a dubious map.

Cheers

Harry

P.S. Please do not characterise my position as ‘anti-science’. I think the scientific method is hands down the best way to discover things about our world. But this is not about science, per se. It is about statistics (which is but a sub-set of the scientific method, with well known attendant limitations).

| Tue January 17, 2012

One other thing I neglected to mention.

Given that the NHANES data just looks at body mass, and not body composition, it could be masking a general ‘fattening’ of the population concomitant with a general loss in lean body mass.

In other words, while it shows that people may have only gained a few kgs in body mass, it does not show if this gain is also accompanied by a loss of lean body mass (which would combine to produce a more significant increase in body fat percentage).

For example, if I gain 3 kgs body mass and keep lean body mass levels constant, that’s probably a modest fat increase for an average male. But if I gain 3 kgs of fat mass AND lose 5 kgs of lean body mass, that’s a net gain of 8 kgs of fat mass, which translates to quite a significant increase in body fat percentage for an average male. The NHANES data is unable to differentiate between these two cases, which reflects the paucity of the data set.

Cheers

Harry

| Wed January 18, 2012

He Harry,

Have you seen this (now popular) study?: http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/307/1/47.short

Some authors suggest this study shows good reasons to simply dump studies that only look at body weight and not composition.

| Wed January 18, 2012

Hi FullDeplex,

Thanks for that reference. Yes, I’ve had a look at the study (abstract only), and it seems to reflect what we’ve known for quite a while with respect to dietary protein’s effect on body composition (i.e. that it promotes the preservation and growth of lean body mass to a greater extent than dietary fats and carbohydrates).

I think it also reflects simple thermo-dynamics, to wit lean body mass is less energy-dense than fat mass (which is why the low protein arms of the study gained less body weight but more fat mass). In other words, 1 pound of fat mass sequesters much more excess energy than 1 pound of lean body mass (or alternatively, a given caloric excess will result in more weight gain if the calories are partitioned to preference lean body mass and less weight gain if the calories are partitioned to preference fat mass).

With respect to studies looking at BMI (and not body composition), I think some of them are still useful, so long as their aims are appropriate. But certainly when looking at obesity in particular (which is explicitly about body composition, not body mass), the sole reliance on BMI stats can be seriously misleading (as per my previous post).

Cheers

Harry

P.S. The well documented rise in sedentary life styles supports the hypothesis that lean body mass losses and fat mass gains are operating in conjunction (meaning that people with a BMI of 30 today may be significantly fatter than people with a BMI of 30 in 1980; a higher body fat percentage, that is).

| Wed January 18, 2012

hmmm.. I wrote a pretty lengthy response here not too long ago.. Where did it go?

| Wed January 18, 2012

Hi Harry,

Just a correction, but the study abstract states: ‘Body fat increased similarly in all 3 protein diet groups’

While you say: ‘the low protein arms of the study gained less body weight but more fat mass’

So you may have to alter the involvement of thermodynamics a bit in your argument. Resting energy expenditure did increase in the higher protein groups though. Increased thermodynamics was involved, but eventually it did not seem have a significant effect on body fat mass.

Anoop | Thu January 19, 2012

Hi Harry,

I am replying to Harry because you seem to genuinely interested and want to have a discussion. I can easily say anecdotal evidences don’t count in a scientific discussion, but I think I need to address it.

Your basis of argument is that people are now heavier than they were before. And I don’t disagree. What we would disagree is the amount of weight gain here.

And when I say 3-5 it is in a decade, the average weight has gone by 24 lbs in the last 45 years. But this is average of a population. In that population there could be obese, severely obese who are pulling the average to higher numbers. And we see that in the trends too. There are sub groups like African Americans who are a gaining a lot more weight than whites. Women and children hasn’t gained much in the last 10 years. So there are variations in the population that doesn’t get picked up by our casual observations.

I think this is what is what is confounding our observations: We see a lot of fat people in airports and Mcdonalds. So fat that we can’t ignore them. So we reach conclusions see America is getting so obese! But what we don’t see how these people were 10-15 years back or how they were when they were kids. These people were either overweight or obese to begin with. But what we miss to see is people who are normal or lean are not gaining much of the weight. We are looking a small sample who is super heavy and we are just extrapolating or spreading the weight gain across the whole population.

If you think about anyone in your family or friends, how many people have drastically changed their appearance. Chubby is always chubby, skinny has remained skinny and fat has always been fat.

Even in the same fattening America, why are there lean , underweight and normal weight people? Are they all watching their diet and eating healthy?

Eat just 50 calories extra a day and after 25 years, you gain 130lbs of fat!! Now what is keeping our weight so stable throughout our years with cheese burgers and unlimited calorie foods around?

For me it s sometimes amazing when people DON’T have an opinion on this topic. This article really change the way people think about obesity. [So thank you for the discussions, even if you don’t disagree. That is the spirit of science!

Anoop | Thu January 19, 2012

Hi Karky,

I am not sure what happened. Since you are a forum member, it should have gone through.

Can you post it again pretty please

| Thu January 19, 2012

I don’t really like using the word “cause” I still believe that our genes haven’t changed much in a long time and when the environment changed to become more obesiogenic, those with susceptible genes started gaining weight. Whether you call genes or environment the “cause” is simply semantics. Obesity probably wouldn’t happen to such a large extent as we see today without both.

You say the overweight category hasn’t changed for 30 years.. Suggesting that those with susceptible genes didn’t become overweight as a result of the environment change, but they were always overweight and they are just increasing their overweight as the environment becomes more obesiogenic (but they were still fat even without an obesiogenic environment. Is this correct, or am I putting words into your mouth?

If this is what you’re saying, I think you are incorrect. Data from a trial in Norway showed that the overweight category has increased. Further, it showed that both the normal, overweight and obese people gained weight to a similar extent. Of course, some people probably were overweight or obese even before the environment changed, but I don’t think they can explain the entire population of overweight and obese people today.

these data are from people who did two health surveys, the first in the 80s and the second in the 90s.. about 20000 men and 20000 women.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16418765

Granted, this is a Norwegian population and not an American one, but I don’t think our genes are THAT different, but maybe they are? And I haven’t seen any data saying that overweight people have stayed the same in the US since the 70s.. And even if it did stay the same, it would only mean that a similar amount of people moving from overweight to obese are moving from normal weight to overweight.

| Sat January 21, 2012

Has anyone else read some of the studies on the correlation of gut microbiota and obesity? http://www.nature.com/ijo/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ijo2011153a.html

It’s very interesting.

Anoop | Sun January 22, 2012

Hi Karky,

I would agree if there was no obesity before the environment changed. We had obesity back before the environment changed. Look at the BMI curve in 1960. 2000 years back Hippocartes wrote about obesity too. And I would agree if normal weight people or overweight people are gaining 30-50lbs and becoming obese. I don’t see both of that happening. I don’t think gaining 10-15lbs due to environment could be called as playing a large role in individual obesity ( though this affects the population data). And I agree the word cause is causing a lot of problems.

Maybe I shouldn’t be so specific. I am just saying in the obsegenic environment people who are in the heavier BMI category are the ones which has gained a lot of weight, 3-4 times what the people on the lower BMI categories. And there might be people who gain 40-50 lbs and become obese, but those are the exceptions. I don’t think anyone can ever say categorically that people were 29 BMI didn’t gain weight like people who were 32 or 33 either.

That is an interesting study, Karky. I don’t know if this is they lacked some of the race-ethnic groups we have in America. Some of the big increase in weight are seen in Black American and Mexican-American women. And the weight gain is a lot more than we see in NHANES data and other studies. My hunch is that the age related weight gain is overlapping the weight gain due to the environment which is making it look bigger than what its is.

In fact I looked at couple of other developed countries and the trends are exactly the same as in US. Here is the obesity trends from New zealand. http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/tracking-obesity-epidemic

Examination of the shifts in the BMI distribution, most readily achieved using the Tukey meandifference plots, shows a fairly consistent pattern across decades, age groups and genders. The pattern that emerges is largely compatible with the mixed model, with little change occurring at the lower percentiles and most of the increase in BMI being concentrated at the higher percentiles (ie, a pattern of increasing skewness). This is mirrored in the rising prevalence of obesity (from 9 to 20 percent among males and 11 to 22 percent among females) accompanied by near stable prevalence of overweight (at approximately 42 percent among males and 27 percent among females). Although differing in detail, the overall pattern is similar for Mäori (for the 19892003 period), among whom the prevalence of obesity rose from 19 to 28 percent (males) and from 20 to 28 percent (females), while the prevalence of overweight remained stable at 30 percent (males) or increased slightly (from 29 to 32 percent) (females).

In essence, much of the weight gain appears to have involved people who were already obese becoming even more obese (leading to a sharp rise in the number of people with extreme obesity from less than 1 percent to almost 3 percent of the total adult population), together with a proportion of people who were already overweight moving up into the obese category, only to be replaced by a similar number of people moving up from the normal weight into the overweight category. So the proportion of the population in the obese category has increased sharply (more than doubled) while that in the normal weight category has decreased moderately (about one-fifth), and that in the overweight category has remained stable.

And good to see someone argue with science than anecdotes and family pictures.

| Sun January 22, 2012

NAHNES data also finds an increase in the overweight category:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9481598?dopt=Abstract

And like I said, all these new obese people must be coming from somewhere, and I’m guessing they come from the overweight group, which means that the overweight group should actually decline if it is just so that those who were already overweight/obese are becoming more so and the normal group was standing still. Thus, even if the overweight group had been standing still the past decades (which it hasn’t, at least not in the US or Norway) there would still have had to have been a movement of people from the normal weight into the overweight group, to balance the movement of people from the overweight to the obese group.

Like I said in my previous post, I don’t doubt that there were obese people long back in the day, but what we see now is not just an increase in those already fat (although that is certainly happening aswell, and to a large extent), it is happening in the normal weight population as well.

Regardless of who are becoming fat, people are becoming more fat in recent years, which fits well with my standing that a change in the environment has increased fatness in the population. I still believe genes and environment has worked together to cause the obesity “epidemic” we see today and I think the environment is of a great importance. And like I argued in the other article discussion, data like x% of the variance in x trait is determined by genetics doesn’t really explain a whole lot of what caused a problem. It just explains the variance of the trait explained by genetics with the environment the world has at the point the data was collected, it doesn’t say anything about what contributed to a change in the trait over time. Though I’m certainly not saying genetics doesn’t have anything to do with it, because it does.

| Mon January 23, 2012

Excellent summary Karky. As you point out, the explanation we really need is the one for the change in the trait (in this case, obesity) over time, not for the prevalence of the trait at one moment in time.

And as I remarked previously, when we look at the problem in this way, the only feasible conclusion is that genetics are a permissive factor in fat gain, while the environment is the regulating factor.

Cheers

Harry

P.S. As an aside, my uncle has worked in clothing manufacturing for the last 45 years…he often speaks about the shift in sales from the smaller sizes to the larger. Essentially there are less people buying small and medium sizes, and more people buying large and extra large sizes. It’s not just that more people are buying the plus sizes; it’s that less people are buying the small sizes in a relationship of concomitant variation (i.e. one value rises to the same extent as the opposite value decreases). This reflects the fact that people are getting fatter across the board, not just moving from obese to very obese.

| Mon January 23, 2012

Hi Anoop,

You said “Eat just 50 calories extra a day and after 25 years, you gain 130lbs of fat!!”

This is not correct according to thermo dynamics.

As you gain weight, your body requires more energy to sustain that higher weight. Moreover, you burn more energy in moving your heavier mass around. As such, the extra 50 calories a day is ‘absorbed’ and a new weight plateau is reached very quickly (i.e. equilibrium).

In order to gain 130 lbs, a huge and progressively increasing surplus of energy must be consumed, in order to counter-act the plateau tendency described above (in the order of 1000s of calories/day extra than the initial diet).

Cheers

Harry

Anoop | Mon January 23, 2012

Karky, why do you think overweight category has gone up n the NHANES data? Look the graph in my article. It hasn’t.

And in the Norway study you posted , yes it is. But as I said how much weight gain are we talking about. If you are right under 29 and if you gain 6 lbs, you will be clinically obese! I am talking about the degree of weight gains here. People aren’t gaining 35-55 lbs you know.

| Mon January 23, 2012

Oh sorry, I actually misread the study :(

But still, like I said, people must have moved from the normal weight to the overweight group if it has remained stable.

Also, I acknowledge that some people are gaining most of the weight, but that doesn’t automatically mean that only genetics caused it. If the population of overweight people has increased their weight making them obese in the last decades, then that has happened after the environment became more obesiogenic, leading their obesiogenic genes to finally lead to a more pronounced obese phenotype

Anoop | Wed January 25, 2012

Hi Karky,

It’s fine. I do it at times too.

And it maybe true even for the NHANES data. It is a cross sectional study and hard to say for sure. I even had spoken with one of the authors of the study.

And I do agree people are gaining weight in every region of the curve. My point is that this is very modest.If overweight people are at 29, they will be obese if they gain around 6-7lbs. And 10-15 lbs as I said is caused by the environment.

If you are normal weight, you will have to gain 50-60lbs to be obese. Is that happening? Clearly not. Are there people who had this happen? Sure, but very few.

| Wed January 25, 2012

I don’t think you can say that x amount of weight gain is caused by the environment and the rest is genetics.. For weight gain, the environment has to be there, if you don’t have food, you don’t have weight gain. And of course, some people will be more susceptible because of their genes. But if a person gains 50lbs, then what happened from the time before to the time after the weight gain? Did the persons genes change? no..

Anoop | Wed January 25, 2012

Hi Karky,

If that’s the case do you agree it is 100% environment? Do you agree? If not, why?

| Wed January 25, 2012

Sorry to beat a dead horse, but I really think the key is understanding the difference between a ‘permissive’ and a ‘regulating’ factor.

A permissive factor allows for some event to occur, but does not of itself bring about the event. It is a necessary condition for the event to have any chance of occurring, but its presence alone is not sufficient to cause the event.

Genetics are permissive with respect to obesity. The right genetic heritage is necessary to allow for obesity (e.g. someone who could not sequester energy into adipocytes could not become fat under any circumstances). However, the genetic capacity (or even predisposition) to store fat in adipocytes is not sufficient to cause obesity (as any cursory survey of concentration camp photographs will show - no fat people, irrespective of genetics).

This brings us to the environment.

The environment regulates the extent to which our genetic predispositions express themselves. In an environment (1) lacking in readily available food, very few, if any, people become obese. In an environment (2) where food is ample, but not particularly palatable or exciting, few people become obese, but some do. In an environment (3) where food is both plentiful and stimulating (e.g. the North American food environment), quite a number of people become obese.

Notice that all three environments assume the same genetic milieu, but provoke different outcomes with respect to obesity.

Genetics sets the stage for the possibility of obesity - the environment regulates the extent to which it actually manifests.

Cheers,

Harry

| Wed January 25, 2012

Any explanation of obesity would have to be universal and independent of time/year/location.

| Wed January 25, 2012

genetics only predispose, certainly other environmental factors would have to trigger this prediposition.

| Wed January 25, 2012

Genes can only explain why some people become overweight/obese.It doesn’t point to why they fatten.

| Wed January 25, 2012

Well, if the genes haven’t changed and the environment has then it would sound like the change in environment is what caused the change in weight. However, that is also a bit incorrect. Let me try out an analogy.

Two buildings are standing next to each other. One of them has been earthquake-proofed, while the other hasn’t. An earthquake comes a long and one building collapses while the other only sustains minor injuries. Now, the earthquake made the building collapse, but it wouldn’t have collapsed if it had been more structurally sound to begin with. So who’s fault is it? The earthquake, or the building engineer? If the building had been earthquake-proofed, it would still stand. However, if there was no earthquake it would also still stand.

You could expand this to an entire city, where buildings take different amounts of damage depending on how they were built.

So the change in environment causes people to gain weight. But what is the underlying factor that decides who gains what amount of weight? That’s the genes, and they are very important as those with a genetic susceptibility probably gain way more than those without one. But without the change in environment, they wouldn’t have started gaining weight. This is because as you say, people find their preset weight and stay there within a very slim margin. I doubt all those who are really fat were never weight stable, they probably were (though maybe still overweight or obese)

But then something changed and they started gaining weight from that set point, why is that? They had the same genes when they were weight stable, but now they are gaining.

And in some cases the environment might not even allow them to reach their true overweight “preset” weight because there is not enough food. The truth is, you cannot have obesity without food and food is in the environment.. Genes are very important in regulating how much food we want, though.

Now I still agree with what seems to be the basic idea of these articles. Which is that overweight people aren’t simply lazy and unhealthy on purpose. One single individual holds little control of his/hers environment (if you think environment in a large scale, like food availability, etc). It’s not as simple as slim people choosing not to eat and obese people choosing to eat. (Free will is something I actually don’t believe in, but that’s a discussion for another time :p)

Anoop | Wed January 25, 2012

Harry,

Your first point is an example of lack of environment. Without environment, the contribution of genetics is zero. Let’s not go back to it again. Let’s give them some food for the sake of the argument here. Is that ok with you? (:-

What you said about the last 2 points about food availability is just a difference between the 1980’s and 1990’s in the graph. More people are being obese because of the north american food, but the average weight increase is around 8lbs in our decade. The fat people were always fat, lean always lean, although 10-15lbs heavier. And to go from normal weight around 23 to just being obese, you have to gain around 50-60lbs! If you want to get around 35, that is around 91 lbs! Do you seriously think people will gain that much weight because there is food around?

We are just disagreeing with the magnitude of increase here.

| Tue February 07, 2012

Anoop,

What do you think about South Asians specifically(since we are on the subject of genes—and I know the ANI/ASI component may matter)? I have read the compartment overflow theory and the ‘thrifty’ genes theory (although mitochondria don’t seem to have a large effect on bodyfat regulation other than their concentration in brown fat) I am a Sri Lankan Tamil who has tried a full ketogenic diet, moderate carb intermittent-fasting, and the low-fat keto diet—of all those, combining fasting with the low-fat keto diet works best for rapid fat loss but it is unsustainable over the long term. I’ve also tried a micronutrient approach, eating mainly things my modern (neolithic) SL ancestors would’ve had available.

http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/1/220.full